October2

Sub-titled How Our Obsession with Stuff is Trashing Our Planet, Our Communities, and Our Health — and a Vision for Change

Sub-titled How Our Obsession with Stuff is Trashing Our Planet, Our Communities, and Our Health — and a Vision for Change

An expansion of the 20 minute Internet film of the same name, the book The Story of Stuff

An expansion of the 20 minute Internet film of the same name, the book The Story of Stuff explores the five facets of the linear economic system in use in North American today: extraction, production, distribution, consumption, and disposal. You might want to watch the video before reading on. I promise: it’s anything but dry.

explores the five facets of the linear economic system in use in North American today: extraction, production, distribution, consumption, and disposal. You might want to watch the video before reading on. I promise: it’s anything but dry.

The overall message of both book and video is that our current economic system is not sustainable—because it is linear, and because it trashes the planet and people at every step. And Leonard makes this point over and over again. Not that the book is repetitious. No, it is that one arrives at the same conclusion at every step of the process, when faced with the facts.

We all recognize that life in 1900 was a great deal different from the way it is now. In the first half of the twentieth century, productivity skyrocketed in ‘developed’ countries: the assembly line reduced the time required to create products and the rapidly diminishing cost of computing power allowed for greater and greater automation.

“With this huge increase in productivity, industrialized nations faced a choice: keep producing roughly the same amount of Stuff as before and work far less, or keep working the same number of hours as before, while continuing to produce as much as possible. As Juliet Schor explains in The Overworked American, after World War II, political and economic leaders—economists, business executives, and even labor union representatives—chose the latter: to keep churning out the “goods,”: keep working full-time, keep up the frenzied pace of an ever-expanding economy.”

In her introduction to her book, Leonard says: “The belief that infinite economic growth is the best strategy for making a better world has become like a secular religion in which all our politicians, economists, and media participate; it is seldom debated, since everyone is supposed to just accept it as true.”

Retailing analyst Victor Lebow, quoted in The Story of Stuff says: “our enormously productive economy…demands that we make consumption our way of life,  that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption…we need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.”

that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption…we need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.”

Leonard says in her film that a staggering 99% of what we bring into our homes today will be disposed of within six months. And our economic model has made this consuming easy: encouraging us with, among other things, buy-now-pay-later, planned & perceived obsolescence, & advertising.

Consumption is the mindset articulated by the chairman of President Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisors in the 1950s. He stated, “The American economy’s ultimate purpose is to produce more consumer goods.”

Think about that for a minute. Wouldn’t it be better, as Leonard points out, if the ultimate purpose of the economy would be to provide quality of life for citizens: good education, health-care, clean air, required infrastructure? As Leonard says: “Accepting and living by sufficiency rather than by excess offers a return to what is, culturally speaking, the human home: to the ancient order of family, community, good work, and a good life; (…) to a daily cadence slow enough to let us watch the sunset and stroll by the water’s edge; to communities worth spending a lifetime in(.)”

Leonard’s scenario is appealing – and many of us have reached a point in our lives where we are ‘simplifying’, often by getting rid of Stuff. “In today’s world, especially in the United States, we throw a ton of Stuff away.  Out it goes—when we don’t know how to repair it, when we want to make room for new Stuff, or because we’re sick of the old Stuff. Sometimes we throw something out thinking it will be easier to replace later than to store it until we need it again. Sometimes we even consider throwing things away a cathartic activity and congratulate ourselves on a productive day of getting Stuff out of the house.”

Out it goes—when we don’t know how to repair it, when we want to make room for new Stuff, or because we’re sick of the old Stuff. Sometimes we throw something out thinking it will be easier to replace later than to store it until we need it again. Sometimes we even consider throwing things away a cathartic activity and congratulate ourselves on a productive day of getting Stuff out of the house.”

Guilty as charged. It appears that simply getting rid of stuff is not the answer.

In the same quick, easy to understand and engaging manner that her film is presented, Leonard examines each step of the linear economic process in detail, providing greater particulars and statistics. Despite the details, the book is very readable (with the exception of the “production” step where the author almost lost me with the lists of toxic chemicals that are inserted into our stuff – the manufacturers’ fault, not the author’s). I liked this book so much that I bought a copy to loan to my friends, and to have on hand to refresh facts in my mind.

Since reading this at the beginning of the summer, I have been extremely conscious of what comes into my house – and even more so of what goes out. We’ve reduced our garbage to about half a bag per week. I have been diligent about finding homes for books, clothing and other items that I would have previously just tossed into the trash. (We’ve discovered that hard cover books are not accepted for recycling here in Nova Scotia but must be set out for ‘garbage’ (read ‘landfill’). We’ve solved this problem by removing all the hard covers and burning them, recycling the now “soft-cover” books.)

And I have talked about this book to whomever will listen.

But not everyone is happy with message of The Story of Stuff . Leonard has been accused of being anti-American, ant-capitalist, and unpatriotic. The American Family Association has condemned the video saying that it “implies Americans are greedy, selfish, cruel to the third world, and ‘use more than our share.’”

. Leonard has been accused of being anti-American, ant-capitalist, and unpatriotic. The American Family Association has condemned the video saying that it “implies Americans are greedy, selfish, cruel to the third world, and ‘use more than our share.’”

On the other side, the Story of Stuff project has been cited as a “successful portrayal of the problems with the consumption cycle”, and hailed as a ”model of clarity and motivation.”

If nothing else, The Story of Stuff has stirred up a great deal of controversy. 5 big stars

I urge you to read this book and talk about it to your family and friends. Do you agree with it or disagree? Is your “back up”? Is what the book promotes even feasible? Would you be willing to adjust to a lower standard of living (one that met all of your needs)? Tell me what you think.

P.S. And, yes, Leonard recognizes that books are a special case. “Books occupy an odd space in my relationship to Stuff: while I feel uncomfortable buying new clothes or electronics, I don’t hesitate to pick up the latest recommended title. I asked my friends about it and found I’m not alone in feeling like books are somehow exempt from the negative connotations of too much Stuff.” You probably feel the same way.

For Canadian readers: The Story of Stuff

The warm and wonderful book

The warm and wonderful book  This

This

Loren Stephens

Loren Stephens

I have watched with interest as Simon at

I have watched with interest as Simon at  If you know A Streetcar Named Desire only from snatched clips or even just your friends’ impersonation of Brando’s “STELLL- AHHHHH!”, as I had, then you’ve missed the quality of this writing. But even if you can’t attend a live production of Streetcar, you can still access the beauty of this play in the written word – a slim 179-page volume that reads quickly and easily and, thanks to many school curricula, continues to be in print.

If you know A Streetcar Named Desire only from snatched clips or even just your friends’ impersonation of Brando’s “STELLL- AHHHHH!”, as I had, then you’ve missed the quality of this writing. But even if you can’t attend a live production of Streetcar, you can still access the beauty of this play in the written word – a slim 179-page volume that reads quickly and easily and, thanks to many school curricula, continues to be in print.

The couple is joined by their daughter Sara who is a chef, which is a happy circumstance considering that they are now in the “gastronomic heartland of France”. (see above)

The couple is joined by their daughter Sara who is a chef, which is a happy circumstance considering that they are now in the “gastronomic heartland of France”. (see above) Heat oil in a large, high-sided skillet over medium-low heat. Add onions and cover. Cook, stirring occasionally, until onions are tender and beginning to turn golden, about 15 minutes.

Heat oil in a large, high-sided skillet over medium-low heat. Add onions and cover. Cook, stirring occasionally, until onions are tender and beginning to turn golden, about 15 minutes.

I didn’t intend to read any picture books this month, but some of my library holds from last year started to arrive, and I couldn’t resist reading them!

I didn’t intend to read any picture books this month, but some of my library holds from last year started to arrive, and I couldn’t resist reading them!

Big, gangly moose is impatient and starts peeking on stage & asking if it’s his turn yet at letter D. Zebra is cool and continues to call letters – and then, after all of Moose’s finagling, chooses Mr. Mouse for the letter M.

Big, gangly moose is impatient and starts peeking on stage & asking if it’s his turn yet at letter D. Zebra is cool and continues to call letters – and then, after all of Moose’s finagling, chooses Mr. Mouse for the letter M. Everybody wants to belong – especially kids. So when a child is “different” from the others in his or her group, it can be easy for them to feel bad about themselves. Todd Parr wants every kid to know “You are special and important just because of being who are”, and he’s written

Everybody wants to belong – especially kids. So when a child is “different” from the others in his or her group, it can be easy for them to feel bad about themselves. Todd Parr wants every kid to know “You are special and important just because of being who are”, and he’s written

I love Robert Frost’s poem

I love Robert Frost’s poem

If you’ve been around the Internet any length of time, no doubt you’ve received one of those Nigerian “I’ve millions in government money that needs to be smuggled out” or “please help this young girl escape her enemies” emails. These scams are called 419s. “The name comes from the section in the Nigerian Criminal Code that deals with obtaining money or goods under false pretenses.” Hence, the title of Canadian writer Will Ferguson’s

If you’ve been around the Internet any length of time, no doubt you’ve received one of those Nigerian “I’ve millions in government money that needs to be smuggled out” or “please help this young girl escape her enemies” emails. These scams are called 419s. “The name comes from the section in the Nigerian Criminal Code that deals with obtaining money or goods under false pretenses.” Hence, the title of Canadian writer Will Ferguson’s  An expansion of the

An expansion of the  that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption…we need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.”

that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption…we need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.”  Out it goes—when we don’t know how to repair it, when we want to make room for new Stuff, or because we’re sick of the old Stuff. Sometimes we throw something out thinking it will be easier to replace later than to store it until we need it again. Sometimes we even consider throwing things away a cathartic activity and congratulate ourselves on a productive day of getting Stuff out of the house.”

Out it goes—when we don’t know how to repair it, when we want to make room for new Stuff, or because we’re sick of the old Stuff. Sometimes we throw something out thinking it will be easier to replace later than to store it until we need it again. Sometimes we even consider throwing things away a cathartic activity and congratulate ourselves on a productive day of getting Stuff out of the house.”

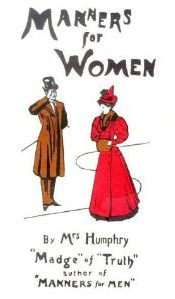

Genuine or a clever counterfeit, Manners for Women certainly shows that some things change:

Genuine or a clever counterfeit, Manners for Women certainly shows that some things change: