UCONTENT: The Information Professional’s Guide to User-Generated Content by Nicholas G. Tomaiuolo – Book Review

![]()

I requested UContent

I requested UContent through Library Thing’s Early Reviewer program, so I can blame only myself if the book wasn’t intended for me. It turns out that “Information Professional” really means librarian and those of us who are book lovers, blog writers and information junkies don’t make the cut. There is a touch of condescension while the author defines his audience. To be fair, though, Tomaiuolo doesn’t exhibit any more professional self-importance than any other expert in any other field would exhibit—perhaps less, while making clear his audience is the professional librarian.

So was there anything here for me? You bet!

Tomaiuolo defines UContent as “the production of content by the general public [such as bloggers] rather than by paid professional and experts in the field”, and not generally considered a reliable source of information. But Tomaiuolo recognizes that there can be nuggets of information out there that can be used by “information professional.’

The material is presented in a logical manner. Each chapter considers a separate UContent source. Topics include blogs, Wikis (including the grand-daddy Wikipedia), podcasts, online product reviews, self-publishing, and citizen journalism. The author also considers information sources within Facebook, Yahoo!Pipes, Flickr and custom search engines. He explains tagging & folksonomies, as well as cybercartography.

Tomaiuolo discusses in some detail the source of information in each category of UContent. His research appears to be extremely thorough (there are copious endnotes in each chapter). He includes an interview in each chapter with a professional in a related field – a professor of journalism, a self-published author, and so on. He also includes well-established on-line sources that will provide updated information before another print edition of this book could be published.

Next, Tomaiuolo performs a surprisingly balanced assessment of each subject’s use, and its relevance for the information professional. He describes how libraries might contribute to the Content (for example, having blogs or being on Facebook) and also how librarians might find relevant information and use it in their own environment, both for their own use and use by the public.

Next, Tomaiuolo performs a surprisingly balanced assessment of each subject’s use, and its relevance for the information professional. He describes how libraries might contribute to the Content (for example, having blogs or being on Facebook) and also how librarians might find relevant information and use it in their own environment, both for their own use and use by the public.

Each chapter of UContent is a veritable goldmine of information. I enjoyed reading it through like narrative non-fiction, although it isn’t that. I consider myself fairly knowledgeable about using the Internet and finding information thereon, but Tomaiuolo taught me lots I didn’t know (what is/are folksonomies anyway, and why should I care?)

This book should become the bible of UContent reference for libraries. It is also a first-rate handbook for students doing research using the web. You’ll want to buy it and refer to it frequently. It’s well worth the investment!

For the rest of us non-professionals, it’s a valuable overview of web content for any blogger or generator of other UContent, plus it’s interesting to read, and it’s full of useful data. For us, I rate it a solid 4 stars.

(Thank you Library Thing Early Reviewers)

For Canadian readers:

UContent: The Information Professional’s Guide to User-Generated Content

But Ez rubs me the wrong way. She doesn’t seem to realize that there’s always more that all of us can do – her included, and that there are no easy answers to the issues facing the environment. Ez’s old couch with the ‘organic stitching’ just doesn’t impress me.

But Ez rubs me the wrong way. She doesn’t seem to realize that there’s always more that all of us can do – her included, and that there are no easy answers to the issues facing the environment. Ez’s old couch with the ‘organic stitching’ just doesn’t impress me. Introducing the piece The $64 Tomato,

Introducing the piece The $64 Tomato,  Tired of the dreary British climate as she and her husband Joe neared retirement, they decided to sell in Britain and move to sunny Spain. The book begins with (Victoria’s) discontent with England, the process of their decision to make the move, and their search for the ideal piece of Spanish real estate (“The House”). Finding a reliable real estate agent was aided greatly by their serendipitous meeting with another ex-pat who had lived in Spain for some time.

Tired of the dreary British climate as she and her husband Joe neared retirement, they decided to sell in Britain and move to sunny Spain. The book begins with (Victoria’s) discontent with England, the process of their decision to make the move, and their search for the ideal piece of Spanish real estate (“The House”). Finding a reliable real estate agent was aided greatly by their serendipitous meeting with another ex-pat who had lived in Spain for some time.

Before I started

Before I started

Just ten pages long , The Landlady is classic Dahl. Young Billy Weaver, newly-appointed apprentice salesman, is sent out from London to Bath on the “slow afternoon train”, and told to find his own lodgings. A Bed & Breakfast sign beckons to him from a brightly-lit window that Billy peeks into. He sees a brightly-colored parrot in a cage, a “pretty little dachshund (…) curled up asleep” in front of the fire burning in the hearth, and a room filled with pleasant furniture.

Just ten pages long , The Landlady is classic Dahl. Young Billy Weaver, newly-appointed apprentice salesman, is sent out from London to Bath on the “slow afternoon train”, and told to find his own lodgings. A Bed & Breakfast sign beckons to him from a brightly-lit window that Billy peeks into. He sees a brightly-colored parrot in a cage, a “pretty little dachshund (…) curled up asleep” in front of the fire burning in the hearth, and a room filled with pleasant furniture. Last week marked the 160th anniversary of the publication of

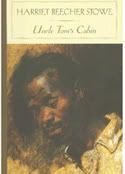

Last week marked the 160th anniversary of the publication of  Mrs. St. Clair reneges on her late husband’s promise and sells the household slaves to a trader. Tom ends up with Simon Legree. Legree is a tyrant who eventually has Tom whipped to death because he stood up to Legree and refused to stop practicing the Christianity he was taught at the Shelbys’.

Mrs. St. Clair reneges on her late husband’s promise and sells the household slaves to a trader. Tom ends up with Simon Legree. Legree is a tyrant who eventually has Tom whipped to death because he stood up to Legree and refused to stop practicing the Christianity he was taught at the Shelbys’. A second problem with this novel is, of course, the stereotypes it helped to popularize – the loving, all-knowing mammy or the pickaninny image of black children, set by Topsy. Stowe makes such sweeping generalizations as “cooking (is) an indigenous talent of the African race”, “the negro is naturally more impressible to religious sentiment than the white”, and “they are a race that children will cling to and assimilate with”. Uncle Tom himself had been criticized for his long-suffering devotion to his white master, and accused of “selling out” to whites. To be fair, and in fact, it’s a different master-slave relationship that drives Tom to suffer stoically as he does—that of his master Jesus Christ.

A second problem with this novel is, of course, the stereotypes it helped to popularize – the loving, all-knowing mammy or the pickaninny image of black children, set by Topsy. Stowe makes such sweeping generalizations as “cooking (is) an indigenous talent of the African race”, “the negro is naturally more impressible to religious sentiment than the white”, and “they are a race that children will cling to and assimilate with”. Uncle Tom himself had been criticized for his long-suffering devotion to his white master, and accused of “selling out” to whites. To be fair, and in fact, it’s a different master-slave relationship that drives Tom to suffer stoically as he does—that of his master Jesus Christ. My birth year, 1954, saw the publication of

My birth year, 1954, saw the publication of  Geisel’s birthday, March 2, has been adopted as the annual date for National Read Across America Day, an initiative on reading created by the National Education Association. Although I’m not a big celebrator of birthdays, I thought it an appropriate day to feature a book that I knew and loved as a child.

Geisel’s birthday, March 2, has been adopted as the annual date for National Read Across America Day, an initiative on reading created by the National Education Association. Although I’m not a big celebrator of birthdays, I thought it an appropriate day to feature a book that I knew and loved as a child.

I intended to post one short story each month this year to keep up with the

I intended to post one short story each month this year to keep up with the  is included in the book

is included in the book  In the sweet Arkansas summer of 1956, preacher Samuel Lake brings his family to his wife Willadee’s ancestral home for an annual get-together.

In the sweet Arkansas summer of 1956, preacher Samuel Lake brings his family to his wife Willadee’s ancestral home for an annual get-together.

Here’s my advice on that: give it a pass. Although I enjoyed watching Stanley Tucci as Puck (proving that I can enjoy watching Stanley Tucci in just about anything), the movie left me cold. It was set at the “turn of the nineteenth century” (which I understood to be 1799-1800), but which is evidently the 1890s. The director couldn’t seem to decide if he was dealing with fairies or with satyrs, complete with orgies and naked (albeit in chest-deep water) nymphs; the classy cat-fight degenerated into a mud wrestling match; and somehow all four human lovers shed every stitch of clothing before awakening the next morning and being told by Theseus (act IV, scene i) to stand up (giving that statement a completely different shade of meaning from the original play.) Note: There are

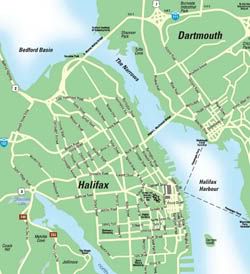

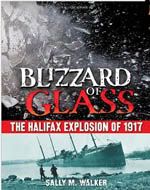

Here’s my advice on that: give it a pass. Although I enjoyed watching Stanley Tucci as Puck (proving that I can enjoy watching Stanley Tucci in just about anything), the movie left me cold. It was set at the “turn of the nineteenth century” (which I understood to be 1799-1800), but which is evidently the 1890s. The director couldn’t seem to decide if he was dealing with fairies or with satyrs, complete with orgies and naked (albeit in chest-deep water) nymphs; the classy cat-fight degenerated into a mud wrestling match; and somehow all four human lovers shed every stitch of clothing before awakening the next morning and being told by Theseus (act IV, scene i) to stand up (giving that statement a completely different shade of meaning from the original play.) Note: There are  It has a deep & generous harbour, and the added bonus of Bedford Basin, just north of the Harbour, fully protected by land. The Harbour and the Basin are connected by a slender strait known as The Narrows. At its narrowest, the passage is less than 500 yards across.

It has a deep & generous harbour, and the added bonus of Bedford Basin, just north of the Harbour, fully protected by land. The Harbour and the Basin are connected by a slender strait known as The Narrows. At its narrowest, the passage is less than 500 yards across.

I realize that I haven’t yet commented on the book

I realize that I haven’t yet commented on the book

Witness what happens when a blogger ventures outside her usual reading genres and takes on a REAL challenge – and then tries to write an intelligent review of the book involved. That’s my situation with

Witness what happens when a blogger ventures outside her usual reading genres and takes on a REAL challenge – and then tries to write an intelligent review of the book involved. That’s my situation with  I did, however, read Pierre Berton’s

I did, however, read Pierre Berton’s